The Name of Plato’s Puzzle

As far as I can see, Plato’s Puzzle fits to a map of the classical constellations for around 1200-1100 BC. The dating is not exact, and may be uncertain plus or minus a few hundred years. What is clear, however, is that it aligns best to a date well before the time that Plato flourished (around 400 BC).

Plato’s Puzzle is named in his honour, since he is the earliest philosopher to describe and explain the polyhedral model of the cosmos. According to Plato’s Timaeus, the tetrahedron was used to form Fire, the octahedron to form Air, the icosahedron to form Water and the cube to form Earth. Together with these four classical elements, Plato assigned a fifth regular solid to the universe itself, which everyone has assumed meant the dodecahedron.

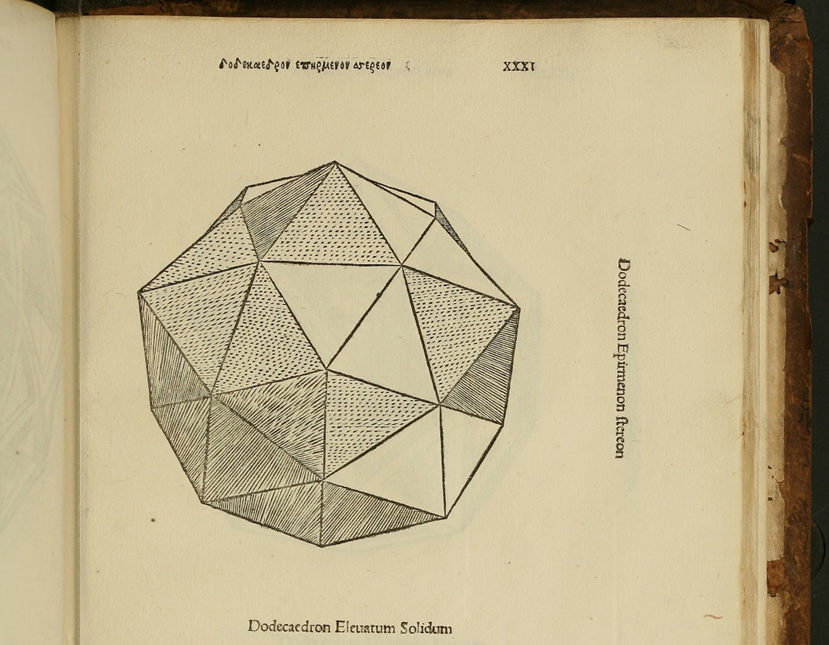

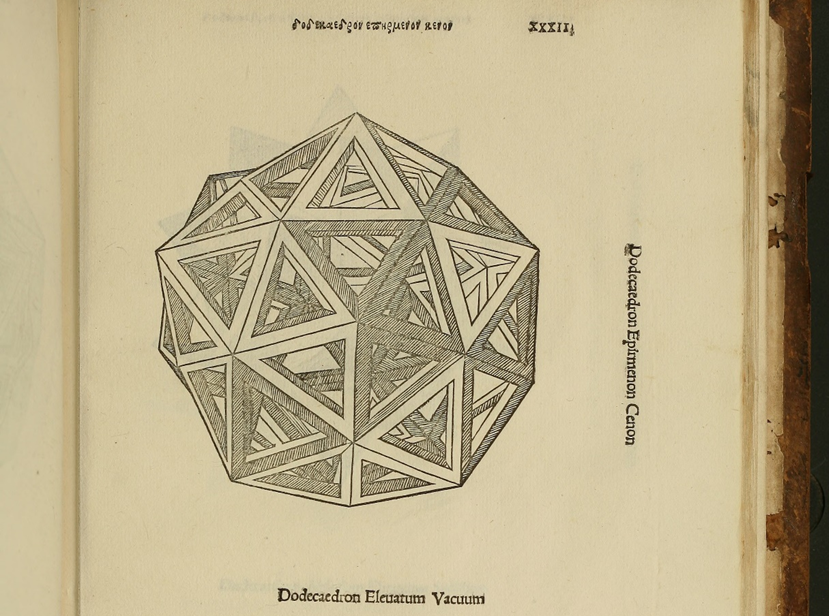

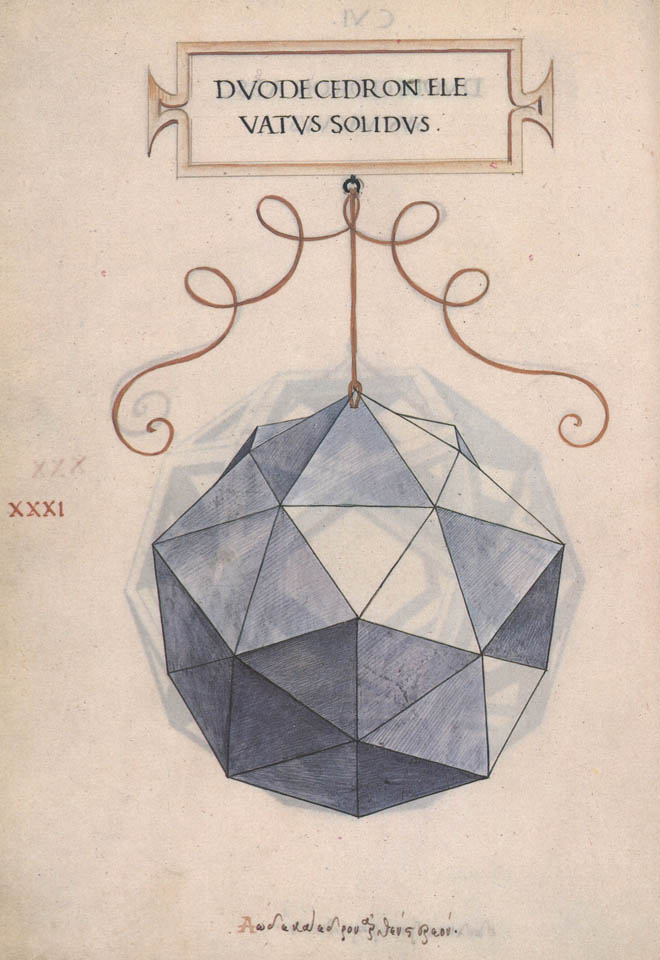

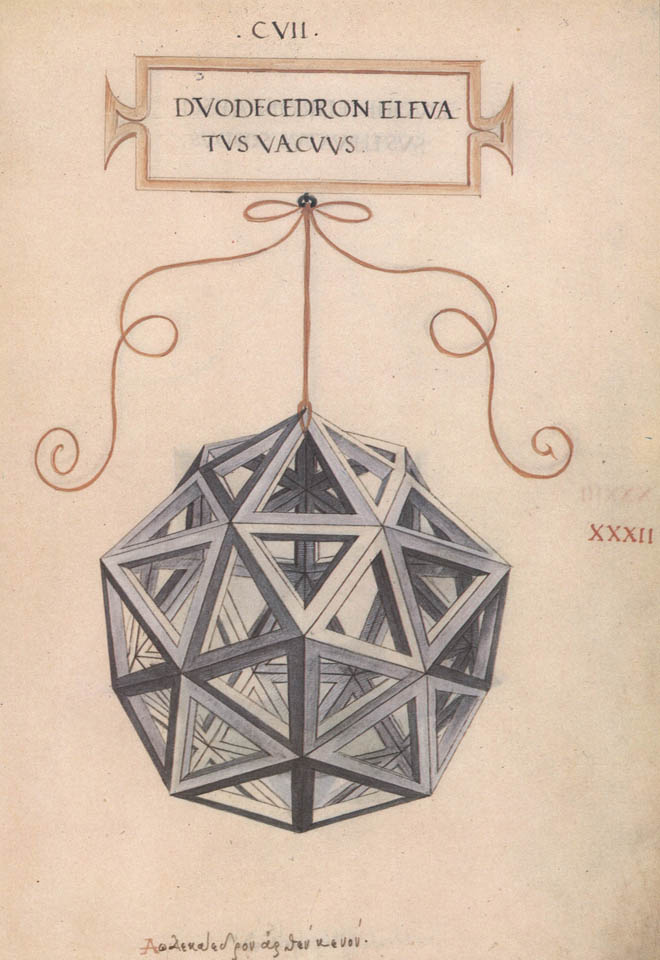

It was in exploring his account that I came to the conclusion that Plato did not only mean the regular dodecahedron. From what I could work out, he also hinted at an even more interesting variant, an elevated dodecahedron made with sixty equilateral triangles. Different degrees of elevation are possible, so I refer to this specific form with equilateral triangles as the ‘orbicular elevated dodecahedron’ (or OED for short), since it appears to have been used as a model of the celestial sphere. If we hold a regular dodecahedron in our hands, then it is possible to ‘see with the mind’ the true world of the OED, and indeed vice versa.

The first person to publish a picture of the OED was Luca Pacioli in his Divina Proportione of 1509, for which he included wood-cut images based on original drawings of around 1497 by Leonardo da Vinci. But it very much looks like Pacioli was not the discover of this shape. And neither was Plato.

The case is similar to the five regular polyhedra listed above. They have come down through history known as the five ‘Platonic Solids’. In fact, an ancient testimony recorded in the margin of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry points out that the description of these solids is not due to Plato, with the cube, tetrahedron and dodecahedron belonging to the Pythagoreans who preceded him.

‘In this book, that is to say the 13th, are written-down/described the so-called Platonic figures, which are not his, three of the mentioned figures are from the Pythagoreans, the cube and the pyramid and the dodecahedron, of Theaetetus are the octahedron and the icosahedron. But they took the surname ‘Platonic’ because he mentioned about them in the Timaeus.’

(En toutō tō bibliō, toutesti tō ig, graphetai ta legomena Platōnos e schemata, ha autou men ouk estin, tria de tōn proeirēmenōn e schēmatōn tōn Puthagoreiōn estin, ho te kubos kai he puramis kai to dōdekaedron, Theaitētou de to te oktaedron kai to eikosaedron. Tēn de prosōnumian elaben Platonos dia to memnēsthai auton en to Timaiō peri auton.)

Euclid, Elementa, Vol. V., ed. I.L. Heiberg, 1888, p. 654. (trans. Mark Sutton, Culture and Cosmos, Vol. 23, part 2. Supplementary Material, p. 33).

Not only that, but it looks like the celestial dodecahedron was designed several centuries before Pythagoras.

Just like the Platonic Solids for which he is already famous, Plato’s Puzzle is therefore named in honour of this greatest of philosophers. He may not have been the originator, but his cryptic account seems to have been setting his readers a puzzle to solve.

Mark Sutton

2 October 2022

|  |

Top tip

To see the original of the scholion on Euclid’s Elements Book XIII, which is translated above, take a look at the 9th century Vatican manuscript Vat. Gr. 190 (traditionally called P) and go to 231r (folio 231 recto).

The text is at the top of the page immediately above EUKLEIDOU: STOICHEIWN: IG.