The story behind

Plato’s Puzzle

Plato’s Puzzle represents the fruits of a discovery made a decade ago. Sitting at the kitchen table, exactly where I am sitting now, I had been thinking about how ancient Greek alchemy and Plato’s geometry of the universe might be linked.

If that sounds a pretty bizarre starting point, it is worth noting that my day-job is as a researcher into ammonia as part of the global nitrogen cycle. It is an exploration of how human alteration of nitrogen flows is leading to pan-dimensional changes to our planet. Using nitrogen compounds, industrialists have helped feed humanity and fuelled multiple wars. At the same time, unintentionally wasted nitrogen resources have caused a plethora of environmental impacts: air pollution, water pollution, climate change, loss of biodiversity and loss of soil quality. Somehow nitrogen is everywhere and invisible, and too often ignored.

Around 2005, I had embarked on a new theme of ammonia research. Not enough people knew about the environmental impacts of nitrogen compounds like ammonia. The idea was that lessons from history could help raise awareness.

The journey that followed ended up crossing multiple fields of endeavour, tracing ammonia wherever it went. I found my mind trekking along the ancient Silk Road, where ammonium salt or ‘sal ammoniac’ was harvested from the edges of volcanic fumaroles and burning coal caves.

In this oldest known nitrogen trade, ammonium was a luxury product, where just 6 kg of nitrogen could buy a human life. Sal ammoniac was used in medicine and metallurgy, and even had the most amazing of names in languages like Sogdian, Armenian and Iranian (noshatr, anushadir, nushadir etc). Translated, these earliest of known names for a nitrogen compound all meant immortal fire !

But this is a story about Plato’s Puzzle, so where is the connection? My journey through the ancient history of ammonia took me along unexpected paths. I found myself exploring ammonia in myth and legend, and ultimately had reluctantly to embrace the dark caverns of ancient Greek and Islamic alchemy. Here I encountered major ethical issues, concluding that public discussion of the chemistry of alchemy must be for another day…

What this hunt for ammonia did show, was that alchemy was almost certainly much older than today’s scholars normally assume. The cosmology of alchemy even suggested that there might be a connection between alchemical theory and Plato’s geometry of the elements.

According to alchemical theory, the classical elements were first purified and then ‘married’. Fire wedded Water, Air wedded Earth, culminating in the great Sacred Marriage of the products. In the process, the alchemical quintessence, the perfected Philosophers’ Stone, was produced.

In his book the Timaeus, Plato also writes about mixing of the elements, where one element can rule (kratei) or triumph (nike) over another, exactly the same terms used by the alchemists for the alchemical marriages. By analogy, it suggested that in remixing Plato’s elements – using his fundamental triangles – it aught to be possible to produce the geometric quintessence: the dodecahedron.

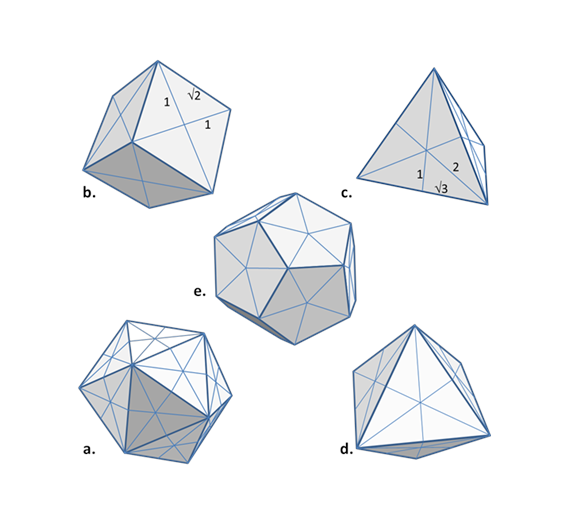

But there is a problem. As any expert in the history of Plato’s geometry will tell you, the dodecahedron is not compatible with the other Platonic Solids. In the case of the tetrahedron of Fire, the icosahedron of Water and the octahedron of Air, these can indeed all be broken down into the fundamental triangles and remixed to produce the other polyhedra. On the face of things, this cannot be done with the cube, which is formed from different triangles. And it cannot be done with the dodecahedron either, where each of its pentagonal faces would divide into yet other triangles.

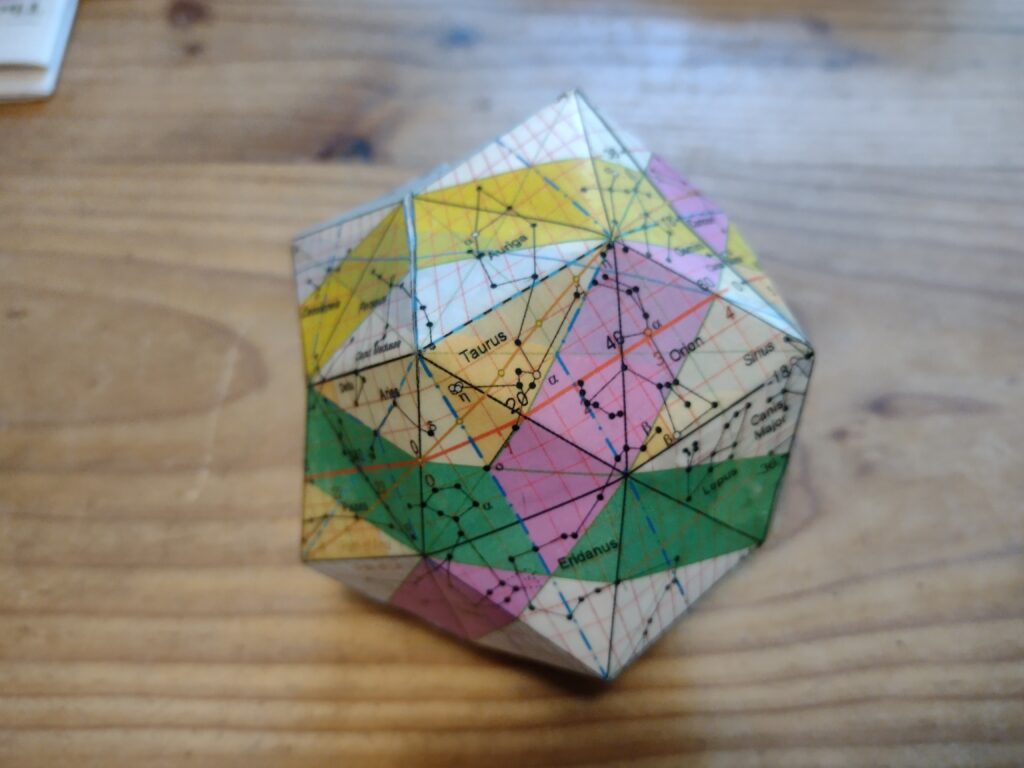

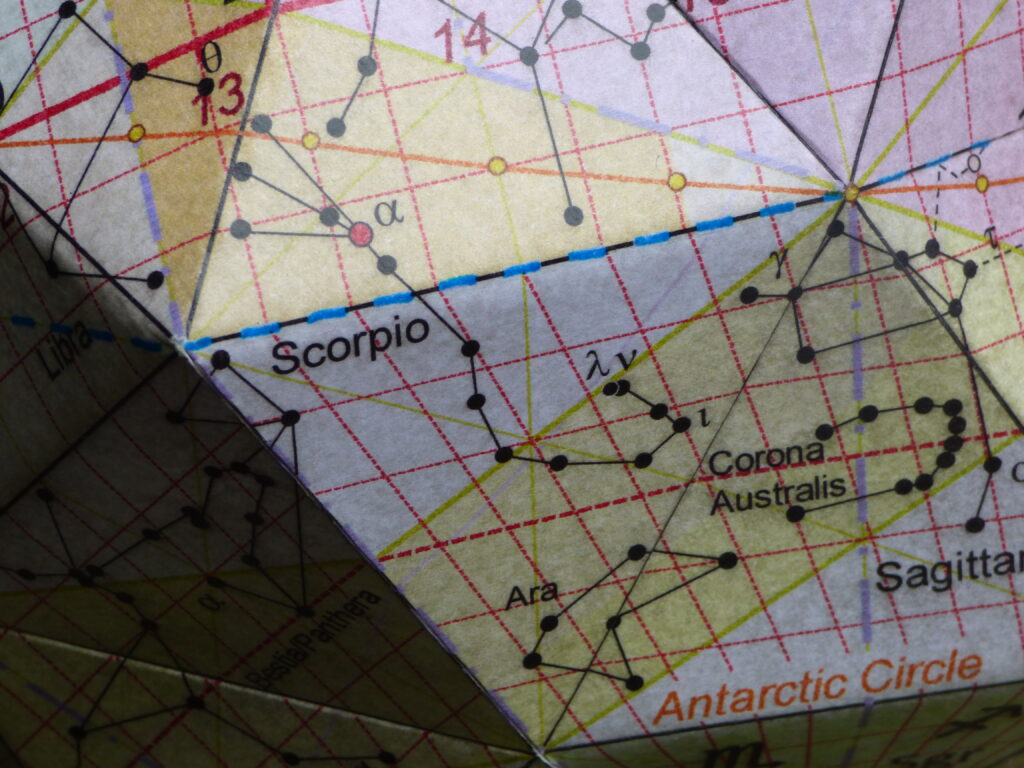

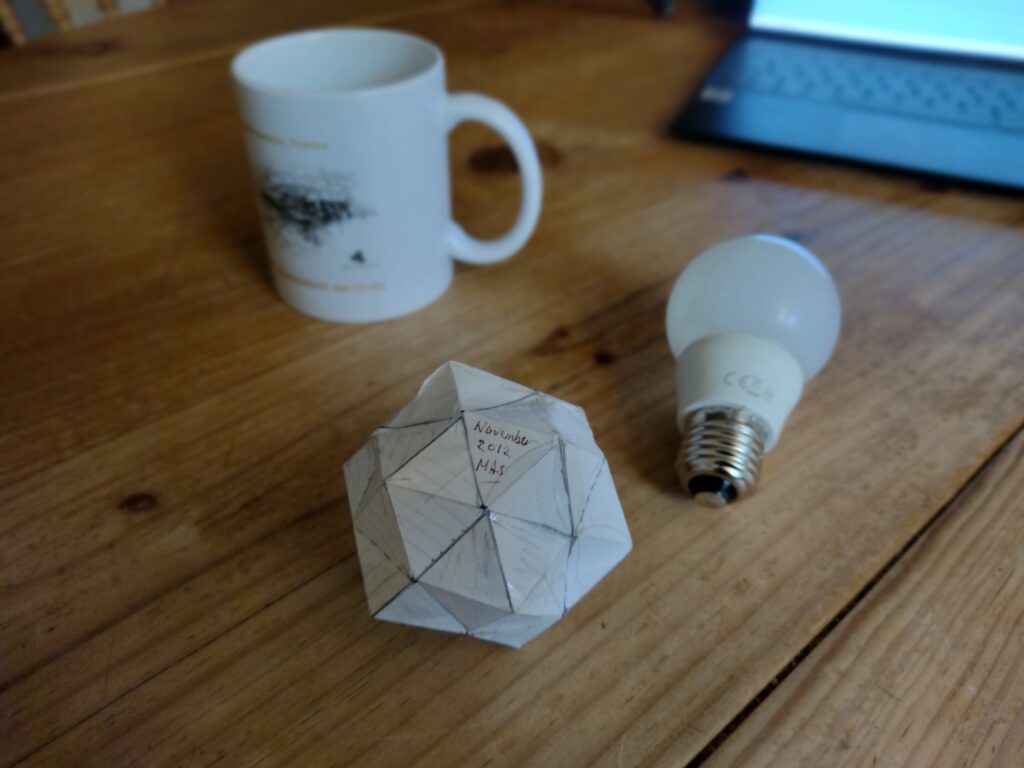

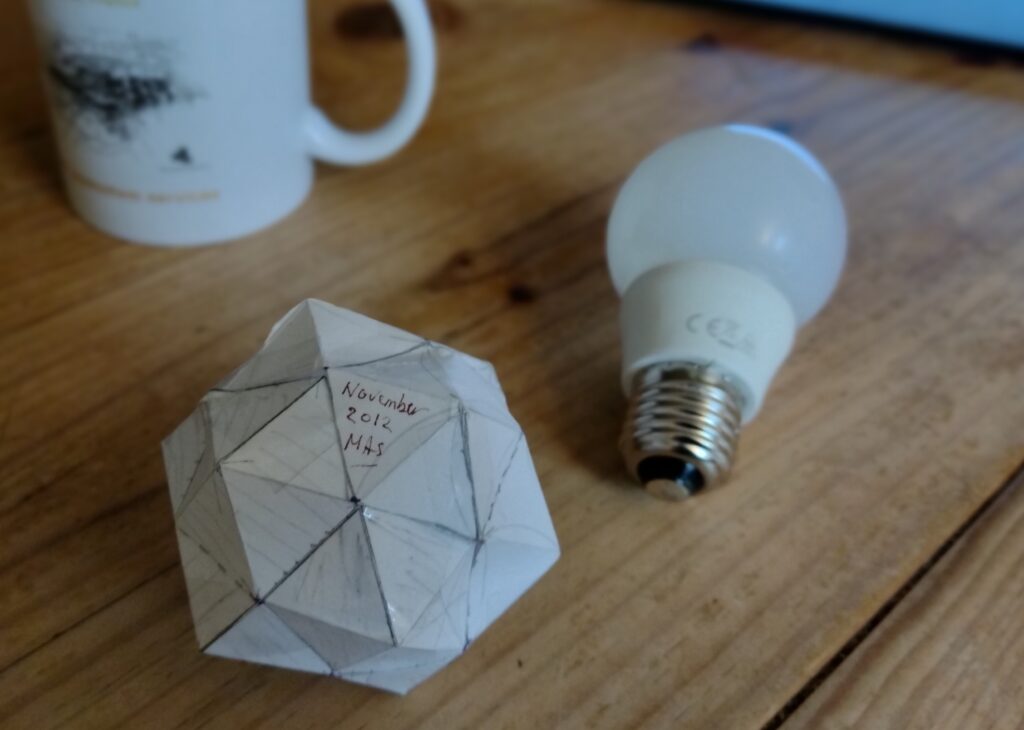

So, what was the solution? Sitting at the kitchen table a decade ago, I cut out twelve hexagons from a piece of paper, removing one equilateral triangle from each hexagon. Folding these gave twelve pentagonal pyramids. By taping them all together, I had made my first elevated dodecahedron.

As for the historical evidence and its links to ancient philosophy, astronomy, cosmology, alchemy and myth, this started yet another journey, which has continued ever since. In Plato’s Puzzle, you find a work in progress, the result of a decade of spare-time reflection. As far as I can see, it is a view of the universe that was invented by ancient philosopher-astronomers several hundred years before Plato. They kept it secret until its details were apparently forgotten. It is now made public for the first time, around 3000 years later.

With more people looking, it is an opportunity to discover yet more layers to Plato’s Puzzle.

As for exactly how ammonia was the key to it all, that must remain a story for another time.

Mark Sutton

2 October 2022